A Filmmaker’s Call to Vote in the EU Elections – blog #1

With only days to go until the European elections (6-9 June 2024, check the dates for your country here), the Federation of European Screen Directors (FERA) brings you a blog series penned by working filmmakers from our board.

The contributions aim to highlight the significance of voting in the European elections and their impact on our shared future. Through their unique perspectives and experience in storytelling, the filmmakers explore the vital role that these elections play in shaping policies, culture, and the artistic and creative landscape across Europe. With this series, we hope to inspire a deeper understanding of and active participation in the democratic process within our community and beyond. Join us on this journey. #Use your vote #Use your voice

The industrialisation of creativity: Putting human connection first

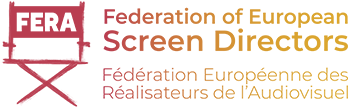

By Bill Anderson (UK), Chair of the FERA Board

Algorithms and generative AI rearrange the past. They no more create story than a burger creates beef. Creative freedom is a particularly human concern – for audiences as much as creators. We quickly tire of stories that feel over-familiar, that we recognise are in the business of merely rearranging old furniture. The intimate human connection we all hope for every time we give ourselves to a story on screen occurs in the moment we realise “This story understands me”. We all yearn to be understood by stories that show us paths into our futures – paths freshly trodden by storytellers trying to make sense of the world they’re living in today.

Even though screen directors are recognised by European law as the primary authors of audiovisual works, the emerging dominance of the streamers and their US working practices are diminishing the director’s role from creative storyteller to prescriptive shot-gatherer. Key elements of the director’s creative freedom are evaporating: intrepid explorers are being turned into bus drivers circling preordained routes. From algorithms determining which stories will be told, to directors being excluded from delivering the audiovisual experience the audience actually engages with, the process of intimate human connection is being industrially dehumanised.

Before the streamers introduced US working practices, directors of high-quality audiovisual series in Europe were usually given around ten working days to complete every hour of their screen story after shooting had finished. The streamers now give us around four – time to merely gather the shots. Why does this matter? Surely directing is all about the shoot – the monocle, the cigar, shouting “Action” and “Cut” into a megaphone?

Not so. For thrift, screen stories are shot out-of-sequence. Directors must skilfully create shots specifically tailored to their vision they must forge after the shoot is over. Imagine you hear that Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of the Mona Lisa is coming to your local gallery: you rush along to discover only a heap of colourful jigsaw pieces that almost fit together next to a hand-written note from the artist apologising for their absence: not the experience you’d hoped for. This is the equivalent of an audiovisual story without authored post-production: it’s missing the director intimately weaving their shots into a compelling narrative, coaxing the sound design, music composition, visual effects, picture grading and sound mixing that together bring to life the jigsaw pieces of the shoot to create the director’s vision of the story.

In the absence of the full creative vision of the director, quality assurance is generated by precedent, algorithm and now AI. No individual takes responsibility. Connection to a fellow human is replaced with connection to a content pipeline. Harvesting eyeballs takes precedence over touching souls.

Offscreen, the same process of dehumanisation is occurring in all walks of life.

We are reduced to data being invisibly mined for profit nudged towards huge monopolies who justify themselves through “market forces” – nothing personal – persuading us to believe they are inevitable, like weather or gravity. But humans have always come together to protect each other with shelters and guard rails – laws agreed by governments to temper the “inevitability” of elements that can do us harm.

As directors and citizens, we try to make sense of the world as we find it in order to live better with our fellow human beings in the immediate present. But some political forces do the precise opposite: they seek to disconnect us from each other by emphasising, even weaponising the return of some mythical lost past or the promise of some utopian future – distracting us from the lives we actually live. Unlike social media, stories can unsettle as well as reinforce our values, burst our bubbles and introduce us to strangers we discover we can connect with: strangers who surprisingly understand us, strangers we need no longer fear.

Since the end of the Second World War the European Parliament has been elected by the citizens of Europe to champion the diverse views and interests of civil society, and as a result war in Europe has often felt very far away. Not now. Growing intolerance and isolation don’t just make us uncivil to each other, they can make us active enemies. But this slide into hostility is not inevitable. We can choose to listen and live together humanely.

From 6-9 June connect with your fellow Europeans, cast your vote and put a human in power who is answerable to you here and now.